Ian McAvity: Be Careful What You Wish for

Ian McAvity: Be Careful What You Wish for

Source: Karen Roche of The Gold Report 11/15/2010

The Gold Report caught up with Deliberations on World Markets Writer Ian McAvity between sessions at the 36th New Orleans Investment Conference, held October 27–30. In fact, Ian was among the experts featured on the conference agenda, graphically updating his big-picture expectations for stocks, gold and the dollar. He continues here in that vein in this Gold Report exclusive.

The Gold Report caught up with Deliberations on World Markets Writer Ian McAvity between sessions at the 36th New Orleans Investment Conference, held October 27–30. In fact, Ian was among the experts featured on the conference agenda, graphically updating his big-picture expectations for stocks, gold and the dollar. He continues here in that vein in this Gold Report exclusive.

The Gold Report: Over time, Ian, you have accurately predicted the bull market in the ’80s, the housing bubble and the credit crisis. So the obvious question: what are your key predictions going forward?

Ian McAvity: Despite people thinking that with all of the bailouts and everything else in the last year somehow the crisis is over, I think basically that the crash of 2007 through 2009 was only the first half of a much larger problem. I don’t want to say the worst is yet to come, but the second half may not be any more pleasant. The housing, banking and financial industry situations have not changed at all. The accountants changed the reporting rules so you just don’t see all the toxic paper still in the banks, and they don’t have to report it.

Since 1971 the dollar has lost something like 3.7% per annum against the Japanese yen. The Japanese continue to buy long-term U.S. Treasury bonds with a coupon of less than 3.7%. That’s a hell of a business. In the ’90s, the argument as to why the Japanese were still buying bonds in spite of the currency losses was that they didn’t have to mark the currency losses to market in their banking system. This is one of the reasons why the Japanese banks went on to have some problems. I like to use that example to point out that we don’t really know what’s going on inside the banks anywhere because they have their own accounting rules. What’s off balance sheets? What’s on balance sheets? What’s the flavor of the month and what flavor do we want to ignore this month? It’s scary.

We don’t know how deep this sewer is, and it really is a sewer. Poor old Bernie Madoff is awfully lonely in jail. A lot of the people involved in the bailouts really should be his cellmates. We’re not entirely sure who got that money, where it went or what it did. The grandchildren of today’s American taxpayers have been handed $3.5 trillion of debt that’s going to hurt them their whole lives.

TGR: Many people, including speakers at this conference, would say that bailouts were necessary so that the whole banking system didn’t collapse. Do you disagree?

IM: Some sort of a bailout was necessary. I’m not sure that a little pain was avoided at the risk of creating greater pain later. Years ago, Lee Iacocca was the champion for getting government money to bail out Chrysler and turning the company around. I had a confrontation with Iacocca, and I told him he did a great job turning the company around, but if the government had allowed the company to fail, the receiver would have sold those factories. Maybe the Japanese would have bought them and maybe it would have resulted in a more successful auto industry that wasn’t saddled with the autoworkers’ unions. It’s the same with the banking system on this occasion. Some of those banks should have been allowed to fail.

TGR: What will be the impact of China, Brazil, India and so on buying less and less U.S. paper?

IM: The degradation of the dollar. The problem is that nobody wants their own currency to take over as the transactions currency for international trade because the minute you get into that position you lose control of a lot of your own domestic monetary policy. So the most significant development this year—and the American media haven’t touched on it—is the agreement between Brazil and China to basically settle their trade balances with each other in reals and renminbi. Those are two of the largest holders of dollars in the world saying that they want to stop accumulating dollars. With your national debt scheduled to go from $13 trillion to $18 trillion, who’s going to buy that other $5 trillion?

TGR: The Fed.

IM: The Fed basically is trying to debauch the purchasing power of the currency. They keep pointing their fingers at China saying that China is artificially manipulating their currency and they have to devalue the USD and revalue the Chinese RMB upward by 40%. China owns $860 billion of paper. Who’s going to give them the $344 billion that they’re being asked to write off? It’s an interesting way to negotiate with your banker.

TGR: You’ve said that before—it’s no way to treat your banker.

IM: Exactly. Another element of this that’s not being addressed in the currency revaluation talk is that all of the surplus countries are putting in capital controls to keep the hot money out. Brazil taxes incoming capital. Everything in Korea is about to have some sort of tax control imposed. China, Singapore and many others are putting tight controls in place that will be a contentious item at the upcoming G20 meeting in Korea.

TGR: When you say hot money. . .

IM: International investment flows. It may be coming from traders, or it may well be coming from corporations trying to redirect their activity. But in essence they’re building walls to keep unwanted currency flows out because they don’t want outside forces driving their currency. It’s the constriction of international currency flows that really becomes a big issue. This is getting back to the 1930s where you get a combination of competitive devaluations and protectionism. Whenever times are tough, the first thing America always talks about is protectionist barriers. We, the great free traders, are free traders only as long as it works our way. The rest of the world is getting a little fed up with that.

TGR: You did some analysis of a dollar crisis in the late ’60s, early ’70s. Do any lessons from that apply today?

IM: If you think about it, we’ve had several dollar crises since the gold window was closed in 1971. From 1946 to 1971, the Bretton Woods Agreement had served as the foundation for the post–World War II monetary system. That was based on the U.S. dollar being tied to the gold price; it was a gold-exchange proxy discipline. The key is that it was an external, apolitical measure.

In the late ’60s, the pressures were building so the central banks ran a gold pool to stabilize the gold price. Finally in 1969 and 1970 the pressures were getting so big that they were losing too much money. So they in turn put the pressure on America to change its policy. This dates from Lyndon Johnson’s guns-and-butter speech in April of 1968. He said we’re going to fight the Vietnam War and we’re going to have the Great Society and we’re not going to raise taxes. The rest of the world asked, “How are you going to pay for it?”

TGR: What’s different today?

IM: Back then, the major holders of dollars—the Arab OPEC oil producers—quadrupled the oil price. I well remember Sheik Yamani making the argument that the U.S. was taking the oil out of the ground and giving them pieces of paper that would become worthless.

TGR: Similar to what China’s saying now.

IM: Exactly. There were two separate rounds of big oil price spikes in the ’70s—first a tripling of the oil price in early 1974, and then another tripling in 1979. The U.S. tried to print its way through it. In October ’78, there was a panicky moment when currency markets were frozen. The German, French, Swiss, Canadian and about half a dozen other central banks went to Washington and said, “You have to stop this decline of the dollar.” A massive coordinated intervention to stop the dollar’s devaluation followed, and when that happened the gold price fell back from $243 to $193, and then turned over the next 15 months and ran up to $850 in January 1980. In fact, it was another currency crisis that got me started in the gold market. In October of ’67, the British pound was devalued from $2.80 to $2.40. At the time that was a huge event. I was working in an office in Montreal, and I remember an old-timer there with tears in his eyes, saying, “There goes the empire.”

TGR: Back to the future, so to speak. What else do you foresee?

IM: Proclaiming the end of the recession, I think, virtually guaranteed a double dip. It’s the same recession from 2007 in my opinion, but if they insist that one bottom was a real bottom, it’s basically going to be a double dip. The U.S. consumer is still buried in debt. The government is trying to fund everything with debt. The notion of borrowing your way out of debt makes no sense. In the long term, they have to effectively deflate the purchasing power money or debauch the currency. This is going to reduce the American standard of living.

I’m wondering how mad the kids who are 20 to 25 coming into the workforce are going to get when they realize the extent of the burdens that have been handed down to them. The American standard of living and stature in the world will go down for many years to come as a result of the recent bailouts and ballooning budget deficits. Brazil, China and India are going to play much more important roles.

TGR: As an investor what should I do with this information?

IM: At the end of the day, on the other side of the deflation of paper asset values, we’ll have inflation, potentially hyperinflation. In that kind of environment, tangible assets are number one. The most viable tangible asset is gold in the context of money that preserves purchasing power. But even quality property that isn’t mired in mortgage paper and questionable titles will preserve some relative purchasing power when a phase of prosperity returns. The tangible asset basis works the same with companies; for instance, paper manufacturers with large forestry reserves have something of enduring value. Those reserves will grow every year as long as it rains and it doesn’t burn down and so on.

TGR: Many of the conference speakers have been talking about the big resource bull market we’re in. Beyond gold, what resources do you consider tangible assets?

IM: If you drop it on your foot and it hurts, that’s tangible. Ross Beaty, a geologist and resource company entrepreneur, is very articulate about the need for copper. Almost anything in the industrial process is going to use some copper. Silver comes in both as an industrial metal and a monetary play as a leveraged proxy for gold. In some respects, silver is like gold on steroids when the wind is blowing in the right direction. But the simple answer is gold.

TGR: You don’t buy the talk about gold being in a bubble at this point?

IM: With every $100 increase in the gold price since it crossed the $400 mark, The Financial Times has published a bubble article. They have no idea what they’re talking about. I find them more amusing than illuminating. In the first place, get gold prices up to new highs in both nominal and real dollars; then you can start talking about a bubble. That would be $2,400 gold, or nearly double the current levels.

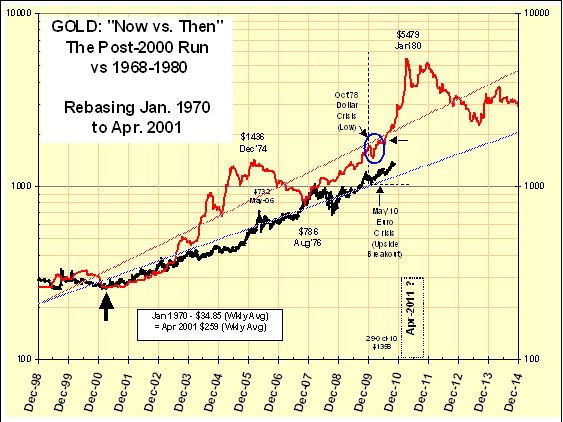

Secondly, I have a cycle model that I’ve been publishing in my Gold Now Versus Then chart for probably seven or eight years.

It overlays the cycle starting in 2000–2001 with the one starting in 1970–1971. If we were to replicate the swings and roundabouts on this, the January 1980 top would translate to about $5,480 in this cycle and that would be scheduled to occur in something like April 2011.

TGR: So the top should hit in April?

IM: No. It would only happen if we were to exactly repeat the past bubble, but that would be impossible to forecast. It’s interesting, though, that in the acceleration phase of the last cycle, the October 1978 dollar crisis fueled the final run-up in gold. In the current cycle, that coincides with all of the hype last spring about the demise of the euro triggered by the Grecian debt crisis and bailout.

For the past five years at all of the different gold shows, I have been saying the final stage of the run in gold would come when the credibility of the currencies themselves came into question. This year we’ve had three bumps of a real currency crisis. First came the euro, and then suddenly the Japanese intervene because their exporters are going to get killed by it. Now everybody’s rejecting the dollar. In essence, we’re replicating the currency environment of 1978 that set the stage for that last bout of inflation. If the market’s going to go crazy, this is when it’s going to happen.

In some respects this currency crisis may be an even bigger one than that of 1978, given the huge holdings of global reserves in the hands of China and the other emerging countries and the growing power they wield through the G20. They’re flexing their muscles now, which could set the stage for a blow-off run comparable to 1980, but I can’t forecast that $5,479 price in April of 2011. It is a useful illustration of what a real bubble run might look like.

TGR: But you think it will happen?

IM: I can’t rule it out. As I say, be careful what you wish for; the economic circumstances resulting from a breakdown of the system would not be pleasant. I don’t want to see it, but I have little confidence in the bureaucratic elites like Geithner et al coming up with any successful resolution.

TGR: What will the changes in the Congress mean for investing?

IM: I don’t have a simple answer. One thing that worries me is a resurgence of optimism that somehow we’ve put the crisis behind us and we’ve printed our way through it. That conclusion is just structurally wrong. The housing market is starting to fall again. A new series of scandals reflects back on the banks. It’s going to get worse.

I think 2011 poses a number of shocks. Coming into December of 2010, we still don’t know what the tax rates are going to be. An awful lot of paychecks in January may have withholdings based on the expiration of the Bush tax cut, so workers all over the country will suddenly be asking, “Why is my paycheck $300 less?” What’s consumer spending going to look like in January? I don’t think consumers will be spending at the levels we saw earlier in the decade, when they converted their houses into ATM machines, for quite a few years to come.

TGR: We talked about your Gold Now Versus Then chart (Chart 1) earlier, but that’s only one of many charts you run in Deliberations on World Markets and use in your presentations. What do you consider some of the best charts?

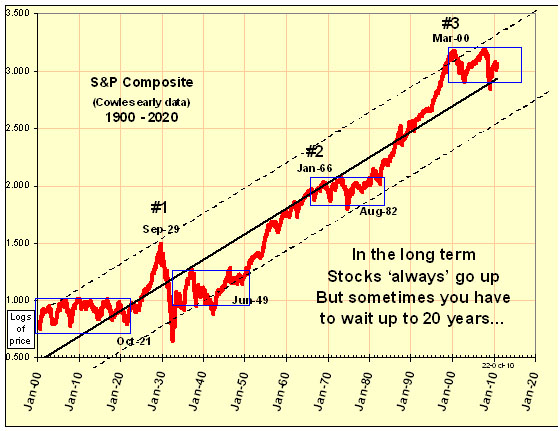

IM: I love showing the S&P Composite 1900 to 2020.

The key point I make from that chart is that the big bull markets that excite people so much really represent only about 38% of those 120 years. The market had three big runs, topping in 1929, 1966 and in 2000. The rest of the time it basically traded sideways for about 17 to 20 years. In essence we’ve been going sideways since 1998.

TGR: If trading sideways is part of a natural course of cycles, what does it mean for investors?

IM: It basically means that investors better recognize there are times to not get carried away with the perception that equities always go up. In the “Other Phases,” the bear market phases tend to run longer and cut deeper than people got used to in the 1982/1999 era. Everybody’s saying we’re in a new bull market. If the S&P and the Dow stay above last April’s highs, they say that’s technical evidence. I’m dubious about that holding, but I’ve been wrong many times before and I could be wrong again.

Over time the markets go up. But if I tell you that you’re going to get the stuffing knocked out of you between now and 2018, will you want to hold on for 2020? Wall Street wants you to buy and hold but they have to sell you something new to buy and hold every year; otherwise they don’t make any money. So basically the biggest risk for many investors is that their long-term plan changes almost every time your broker calls.

TGR: How much do you rely on what you see in the charts versus your knowledge about human nature and what’s happening in the geopolitical world?

IM: It’s basically 40 years of experience in one big cocktail, a mix that includes the assumption that every single price at any moment in time contains all the hopes and fears of everybody who knows or thinks they know whatever evidence is out there. At the end of the day if the background fundamentals are uncertain but a pattern is visible where price has gone up and up and up, it tells me that the buyers dominate at that point. In that sense, the technicals would be the purist measure.

Having accumulated scar tissue over the years, I’m inclined toward the fundamentals as well. Prices walk on a technical leg and a fundamental leg. It would be naïve to ignore either, but when in doubt I’ll bet on technical analysis of price trends. Where I probably differ from most of my age group until recently, I’ve always focused on the international markets. I was publishing global market charts back in the 1970s, long before John Murphy published his book on Intermarket Relationships. I didn’t come up with that label, but having been brought up in Montreal and Toronto, I was always in touch with the British markets. For years I published charts showing that London led. New York followed. Tokyo lagged and the Canadian market lagged New York by one leg. I had an article on the Canada/New York lag published in Barron’s back in 1976, illustrating that when Canada actually had its highs, New York was often making its first failing bear market rally top before a decline. That worked from the 1950s into the early 1980s.

But when you do that kind of analysis you get pretty cynical pretty quickly; the operative phrase today would be, “Every time I find the key, they change the lock”—because it ain’t easy. It’s really a question of balancing the different influences. For most investors, the simple discipline would be to watch a couple of longer-term moving averages under a trend. If the price is above the 200-day moving average, that’s governing the trend. If something you own goes through its 200-day moving average, stop and think and do some homework. Many free Internet charting services let you customize a chart, and a good mix that I suggest for patient longer-term investors is a combination of a 50-day and a 200-day moving average. For as long as the 50 is above or below the 200, that trend is going to continue for longer than you think. It’s a lagging confirmation tool, not a short-term trading idea. When they cross, the market is telling you that something’s changing and you may want to revisit and rethink your portfolio.

TGR: You also have analyzed the relationship between gold mining equities and gold bullion. Can you explain that to our readers?

IM: I refer to it as the shares-to-metal ratio because prior to 1975 when Americans could not own gold, North American gold mining shares typically were very expensive as the proxy for owning gold. At times, the expectation levels that get priced in are just outrageous. The shares-to-metal ratio, which I’ve calculated going back to the 1930s, peaked in 2003 when the gold price went through $400.

When gold ran from 1971 to 1980, the miners’ shares could not keep up with it. The Miners Index in Chart 4 is a composite of the leading miners of the day, with the modern period from 1993 being the GDM Index that underlies the popular GDX ETF. The great growth and transformation of the Industry came after gold stabilized, from 1982 to 1996. That was followed by a vicious secular bear cycle that bottomed in 2000/01.

The gold-shares-to-metal ratio hit its highest level of expectations in December 2003, as gold was moving through $420 to confirm this new cycle.

The irony in this cycle is that the gold mining industry has consolidated into bigger and bigger companies, a complete flip from the industry’s history. They’re not finding many big deposits anymore. Investment bankers, in my view, have been harvesting the industry by promoting takeovers where the big miner issues a bunch of stock to absorb the miner that’s made a discovery in the hope that the new deposit will grow. The 50% premium over market that the bigger miner is willing to pay to replace the reserves they just mined, and capture some growth later, is popular with those being acquired, but in the meantime, yesterday’s shareholders of the major just got diluted.

TGR: Right.

IM: The major gold mining stocks are barely keeping up with the gold price since the crash. Yet all these new billionaires such as John Paulson are running around singing the gold song. The theory is that the miners always will make more money than the selling price of the commodity they mine. It sounds great, and it makes all kinds of economic sense—but I have a history of charts going back to the 1930s that says it happens for a little while but it’s not a sustained trend. The miners right now are heading into a period during which they’ll probably outperform the metal price. But if I’m right about the S&P 500 going back and testing the lows of March of ’09, I’d have to remind you that gold mining shares are just shares. When the market goes down they’re going down with it, and in such declines the metal price is likely to decline a lot less. Remember that volatility works both ways.

TGR: When do you foresee the S&P 500 going back and testing those lows?

IM: I expect the next six to nine months to be an interesting period. During this window of time, with the gold price possibly spiking in the second quarter, I’m very concerned about how the new Congress will work with the White House. There’s an awful lot of stuff coming up in the first half that makes me very nervous. I don’t know how it’s going to turn out, and I have little confidence that it will be much more than political posturing with an eye to the 2012 Presidential election. I just know that I’m very nervous.

TGR: What advice would you offer under such circumstances?

IM: Don’t get carried away by recently rising prices. In this climate, take some money off the table. Put your house in order, i.e., reduce debt. Don’t get yourself in a situation where a sudden move in the market can cause margin calls that might blow up your portfolio. Don’t buy into all the hype about quantitative easing, expecting to see money that’s not being absorbed in the economy to be sloshing around the financial markets.

People also have to know who they are and what they are. Someone will tell me, “Oh, I bought gold because the world’s going to hell and it will ultimately go to $5,000.” Then he’ll turn around and say, “Gee, I have so much gold in my account and the 10-day moving average just crossed the 50-day moving average.” I’m saying, “So?” They say, “It’s going to pull back $100 or $200.” I say, “So? You bought it because it’s going to $5,000, and now you’re worried about a $100 or $200 (10% or 15%) setback during a prospective 300% run?” Are you a trader or an investor? You’re unlikely to be successful at both. Some people “get it” when I ask if they cancel the fire insurance on their house because they haven’t had a fire lately…

TGR: But with the market going sideways for 17 to 20 years after a boom, as you mentioned earlier, don’t you have to be a trader on some level?

IM: You should be an investor with a cyclical focus. When I talk about going sideways, I don’t think the four-year cycle rhythm is going to go away. We had very good bottoms in 2003, and had a very good bottom in the spring of 2009. But you’ve already had 18 months to bounce back from that bottom. If you reach another bottom, it doesn’t mean that the S&P is somehow going to blow up and go away. There will be good bottoms. The harsh part of the 2009 bottom was that it happened almost too fast.

TGR: Right.

IM: That was partly due to all the bailouts and the amount of money being thrown in. Maybe that’s something we’ll have to learn to live with—but by the time I was comfortable with that bottom, it was practically over. I’m not one to get out there and start catching falling knives, so I missed a good part of that bottom because the whole thing was over way too fast. But then again, a really good bottom never gives you a second chance. It just keeps on going.

TGR: Because you’re known for your predictions, Ian, are you telling investors that we might be near a top in this market rebound from that bottom?

IM: Yes. I tell people that for $3.5 trillion in new debt for your grandchildren to worry about, “they” bought a pretty good rebound that’s about 20 months old, and running out of gas.

TGR: And then have another pullback?

IM: Yes. I don’t think you’ll see the October 2007 high on the S&P, though. Not again for several years.

TGR: Will we go down to the 2009 bottom?

IM: Yes, I expect to see it tested, and possibly even be broken. If you think in terms of the broad range of 700 to 1,500 over past decade on the S&P, we’re currently around 1,200. We’re more likely to be in the 700 area rather than adding another couple of hundred from here. Think in terms of 300 points or less upside potential versus 500 or more points of downside risk. I think we’re much closer to a top as we enter 2011. And I really do worry about the risk of making a lower low than the March 2009 low—but that is a risk factor rather than a prediction.

TGR: So your general feeling is that we’ll pull back the economy in the U.S. particularly. . .

IM: Waves of fear will be coming up, because for $3.5 trillion they bought a hell of a bounce. But most of that bounce is behind us at this stage. And somehow when something people own is actually down 50%, they tend to think of that as something more than a pullback. I’ve often referred to it as a point in the market cycle that calls for a national diaper change.

The reported “advance” GDP growth of 2.0% for the latest quarter was the smallest positive number since the March 2009 lows. Seven of the last ten “Advance” GDP estimates have been revised lower as they progressed to a final reading. I think the economy is slowing a lost faster than people realize. Few ask what changed from early last summer when Bernanke was talking about withdrawing the quantitative easing liquidity, and only a few months later he’s done a 180 and is pouring in another round of it.

TGR: Ian, this has certainly been informative. Thanks for your time.

Ian McAvity, involved in the world of finance for more than 40 years as a banker, broker, independent advisor and consultant, has produced Deliberations on World Markets since 1972. He specializes in the technical analysis of international equity, foreign exchange and precious metals markets, and has been a featured speaker at investment conferences and technical analyst society gatherings in the U.S., Canada, and Europe over the past 36 years.

Ian has been a director of Central Fund of Canada, the original stock exchange tradable gold and silver bullion entity listed on NYSE-Arca since 1983; a trustee of NYSE-Arca-listed Central Gold Trust since its 2003 launch; and a trustee of TSX-listed Silver Bullion Trust (TSX:SBT.U) since its 2009 launch.

In the 1980s he was extremely active in financing junior exploration companies, but cut back that activity in the late 1990s. A member of the board of directors of Duncan Park Holdings since 2004, Ian inherited this junior exploration company’s top job upon the death of its president in 2007. He has revitalized the company with an earn-in deal on a block of claims in Canada’s well-known Red Lake Mining District. As Ian describes it: “You couldn’t ask for a better address to explore for gold than to be within sight of the head frame of the richest mine in the country.”

Want to read more exclusive Gold Report interviews like this? Sign up for our free e-newsletter, and you’ll learn when new articles have been published. To see a list of recent interviews with industry analysts and commentators, visit our Expert Insights page.

DISCLOSURE:

1) Karen Roche of The Gold Report conducted this interview. She personally and/or her family own the following companies mentioned in this interview: None.

2) The following companies mentioned in the interview are sponsors of The Gold Report: None.

3) Ian McAvity: I personally and/or my family own shares of the following companies mentioned in this interview or the biographic notes: Central Fund of Canada Limited, Central Gold Trust, Silver Bullion Trust, Duncan Park Holdings Corporation. I am a director or trustee, and shareholder or unit-holder and receive fees from each of these companies.